|

| The Golden Till - Forward |

|

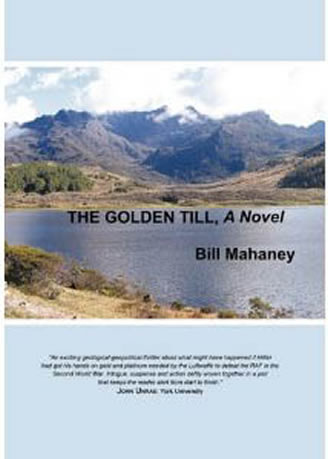

Available at Amazon.com Published by iUniverse, Bloomington, Indiana, 2010 Frontispiece: Lago Mucubaji in the Eastern

Mérida Andes is a typical glacial lake impounded by moraines

dating from the last glaciation. The main transverse ridge in the

middle ground is a recessional moraine deposited by receding ice

which moved up-valley and off to the left at the end of the last

ice age. The cirque (glacial amphitheater) in the background once

housed a small feeder glacier that fed into the main ice stream.

The view here is similar in size and scope to lakes and deposits

in the Coromoto Valley, the main artery leading to the Humboldt

Massif at ~5000 meters elevation. Located about 45-km to the south

on the high spine of the Andes, the valley below the Humboldt Glacier

is the type locality of fictional gold and platinum placer deposits,

which form the center of gravity of this story as it unfolds. |

by Bill

Mahaney Available at Amazon.com Author’s Note Surely few natural historians have travelled as far and learned as much as Alexander von Humboldt. His explorations, together with Aimé Bonpland in the Americas in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, stand as one of the pillars of scientific achievement, breaking new ground in every field of physical and biological thought. Von Humboldt’s gold-platinum find, if it did exist, would have changed the course of human history, just as his Explorations and Kosmos changed the course of exploration and scientific thought. FOREWORD The inspiration for this book came from several years of studying glaciers, especially the limits of glaciation and glacial dynamics, in the Andes of Venezuela, Bolivia and Argentina. During this time, I wondered what it must have taken to drive explorers extraordinaire, like Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland, to seek out, describe and study the high Andean Mountains, a five-year project. Their only prospect of success would be the publication of a natural history of one of the largest and most imposing mountain chains on earth. During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries travel and communications in the northern Andes would have been slow. With a primitive road system, and movement restricted to horse and carriage or cart, movement in the countryside was restricted. Travel in the mountains meant penetrating the dense cloud forest between 1500 and 3000 meters above sea level, to reach the páramo or South American alpine, the high Andean landscape complete with raw-edged tussock grasses and Espeletia (Frailejón). In the Andes, the Frailejón blooms as a long-leafed tall plant with an almost iridescent green hue, very similar in form to the Senecio of the East African mountains. Had von Humboldt and Bonpland attempted to explore the cloud forest they would have had to break off their lowland explorations and trek through the scrub semi-deciduous woodland adjacent to the giant inland Maracaibo Lake. In von Humboldt’s time this lower vegetation zone was inhabited by the Motilone, a tribe of blowgun carrying natives known for their fierce protective and warlike nature, which they had developed from contact with Spanish invaders. Had they attempted to explore the high mountains, Von Humboldt and Bonpland would have had, first to penetrate this formidable native barrier, and then make their way through the cloud forest to reach the glaciers of the high páramo. In reality, they bypassed the Venezuelan Andes to explore much of the Amazon Basin and later the high mountains of Ecuador. The cloud forest, one of the densest on earth, is every bit the equal of the bamboo-Podocarpus forests of East Africa, where, at best, one can see a distance of two or three meters. With little sunlight passing through the thick foliage, direction is only possible with a compass. Gold in placer deposits and platinum veins in bedrock in the Mérida Andes are strictly fictional. Till, the sediment emplaced by glaciers, is often studied for its heavy mineral content (including gold), and much gold is dropped or emplaced as placers around the margin of glaciation. In the story, von Humboldt and Bonpland find gold and platinum, but keep the location secret to avoid a gold rush. The find remains a secret until the logs and notes made by von Humboldt turn up later on in Europe. German agents discover von Humboldt’s notes and samples in a European museum, a prime bit of military intelligence that adds momentum to the Third Reich’s expanding war machine. Since the platinum contains iridium, a platinum based metal important in the manufacture of aircraft carburettors, the presence of this strategic material leads to a major raid on the Andes to recover the ore. Iridium, a hard, lustrous silver-colored metal, stable in both air and water, and inert to all acids is the principal component of special alloys used in aircraft internal combustion engines. Its high boiling point, low thermal expansion and rare occurrence make it an extremely valuable and strategic material. In 1939, the major source of this metal was in Alaska, and the ore mined at Goodnews Bay was sold directly to Britain for use in the new Spitfire, which would soon replace the Hurricane as the operational fighter aircraft of the RAF. Herein is the crux of the plot: the ultimate struggle of two ideologies, both believing they are on the side of right, backed by rex and regula of their individual nations, to recover the Andean gold-platinum. Once recovered, the precious ore would provide their governments with the added financial and military might to win the forthcoming world struggle.

GOLD AND PLATINUM, SOUGHT AFTER TO SHORE UP THE GERMAN CENTRAL BANK AND TO BUILD HIGH PERFORMANCE CARBURETORS FOR THE MESSERSCHMITT, BECOME AN OBSESSION OF THE GERMAN MILITARY. IN THE SUMMER OF 1939, GERMANY SENDS A SUBMARINE FORCE WITH PARATROOPERS TO VENEZUELA, TO RECOVER VON HUMBOLDT’S GOLD AND PLATINUM. ONLY JACK FORD, AN AMERICAN

PROFESSOR OF ARCHAEOLOGY, STANDS IN THE WAY OF A SUCCESSFUL RECOVERY. April, 1939. Students milled around in the hall outside the lecture room at the far end of the Institute waiting for classes to start. One of the resident archaeologists in the museum, Jack Ford, stopped briefly to look at the crowd of students. Not spotting any familiar faces in the crowd, he threaded a path that would take him to his laboratory. It seemed to him that student numbers had swelled somewhat during the last few months while he had been off recovering artifacts in South America. At the far end of the hallway, he noticed Reuben Porter, a cantankerous and windy colleague coming out of his office, fumbling with his keys. Not wanting to indulge him, Jack crossed over to the door leading to the second floor, and bounded up the stairs two at a time. At the top he turned left, hoping he had evaded Reuben, and walked quickly to his office at the end of the long corridor. He had an hour before his class started and wasting time on idle conversation with one of the gossip artists in the place was the very last thing he wanted to do. Pulling on his lab coat, Jack settled onto a stool in front of his laboratory bench and searched for the keys to the lab cabinet. He unlocked the storage cabinet and took out the latest gold specimens, icons collected from a site near Machu Picchu in Peru. He placed them on the table and studied them at length. These icons had nearly cost him his life and he was lucky to have escaped in one piece, to return to the normalcy of lecturing in anthropology. Staring at these ancient relics, he asked himself, half out loud, “What is it that makes them so sought after, so valuable?” The earth around them, in which they were found encased, might yield valuable clues to environmental change and even age, but the relics, people would fight over or even die for. For many, they were prized beyond all value. A knock at the door interrupted Jack’s reverie and brought Cedric Caine, wearing a broad grin, into the laboratory. His former professor, Cedric was also his colleague, trusted friend and advisor. An archaeologist in his own right, with an international reputation, Cedric spent most of his time trying to finance Jack’s excavations in South America and elsewhere around the globe. Jack studied his face, noting a mixture of anticipation and fear, borne of wonder that the icons had been recovered at all and anxiety over what the museum board would say about how they had been collected. Jack had no doubt Cedric would eventually get round to asking where and how he had managed to collect the icons. Above all, he knew he would have to come up with some creative answers. Yes, he ought to smile, Jack thought. The tremendous find brought back to the museum from Peru would ratchet the museum up a notch or two in the academic world. They were the first icons of their kind in North America and supposedly unattainable despite vigorous searching by many archaeologists all over the world. Jack had recovered the Incan gold icons from sites radiating out of the center of Inca culture at Machu Picchu, a civilization destroyed by the Spanish invasion of the Sixteenth Century. Turning to look at Cedric once again, Jack could see he was stupefied, mouth open and clearly unable to speak, overawed by the beauty of the icons that lay before him. Anticipating Cedric’s quizzical look, Jack remarked, “Yes, Cedric, Dad will analyze the gold content. The conquistadors searched for the source of the gold, but could never find it.” “Does your father know you are back in town?” “I talked with Dad last night. He’ll be in later today to do an analysis on the samples but I have no doubt the gold content is the purest to have ever come out of South America. Truly beautiful and truly amazing.” The Incas had not only found the placers, but exploited them by mining the gold and little silver (called platina by the Spanish, now called platinum), producing some of the most beautiful art forms ever made in South America. As they sat looking at the figures, Jack thought, Pizarro had searched for the source of the gold, but could never find it; he didn’t understand the geology well enough to put it together. Concentrating on the vein gold, when most of the accessible sites were at lower elevations in the placers, was a big mistake. As Cedric continued to study the figures, he turned them around to inspect every facet, his fingers following every suture. Jack watched the intensity build in Cedric’s face, thinking, The people who made them were extraordinary craftsmen. Their descendants worshipped the icons, believing they contained supernatural powers so terrible they could be unleashed on nonbelievers. Just then Cedric looked at Jack and remarked, “The Indians will have put a curse on you, especially since you don’t believe in the supernatural.” “We are not ‘believers’ exactly, Cedric, but most of us respect the religious significance of the icons. I certainly appreciate their beauty and exquisite craftsmanship.” Jack watched Cedric’s reaction, thinking he might be spooked by the thought of a curse, but Cedric seemed willing to drop the subject. The gold alpaca and llama statues, together with a wooden ceremonial vase and star-headed mace embellished with gold, formed the newest additions to the museum collection from Machu Picchu, the last Inca refuge. Looking at Cedric, Jack pronounced, “Dad will ask about the source of the gold and this time I think I know the answer. The Incas were collecting it around the margins of the great Pleistocene glaciers in the Andes. Find the great glacial terminal moraines and you have the placers. We dug two of them and brought the samples back that should prove the theory.” Watching Cedric grow more intense, Jack waited a few precious seconds and added, “Want to finance an expedition to find the source of the gold?” Cedric weighed the question for a minute or two, and then, stammering slightly, asserted, “Can you find it Jack, do you think, the actual source? If you could match the source to the gold figures it would be a coup for the museum.” “It can be done, Cedric, it can be done,” Jack confirmed, with a wry smile. The two scientists looked long and hard at the figures without uttering a word, and then Jack locked them away in the sample cabinet. As Cedric went off to a committee meeting, Jack thought, At least I am spared meetings; teaching is wearying enough and nothing like field work where discovery can come at any time. An important find might catapult one’s reputation, from the dark abyss of the unknown, to the known, perhaps even the widely known. But, fame is not the driving force, he thought. It’s the adrenalin rush of the find, the exuberance brought about by new evidence that ultimately provides proof for a new theory. Debunking a popular theory, advanced by someone who has never dug a site, has a certain appeal. And, oh yes, there are many archaeologists with clean, unworn hands, Jack thought. Archaeology, the embodiment of interdisciplinary science, is the field of learning which draws upon knowledge in many disciplines, from physics to history. Thinking of the interconnectedness of several disciplines, Jack was strangely reminded of Alexander von Humboldt, the great German explorer-scientist of the New World. The natural sciences had come a long way from the pioneering days of von Humboldt and Jack wondered why he had suddenly thought of the New World and von Humboldt. It must be the icons, he told himself. Then, after thinking about the icons for a short time, he puzzled over what the great explorer would have done with them had he found them. As Jack thought more about it he decided to write up the results and publish when the time was right. Dropping the thought from his mind, he checked to insure the gold figures were locked safely in the cabinet, and picked up his briefcase. Looking at his watch Jack realized he had to hurry to get to class. While chuckling as he walked off to class, Jack thought, it’s getting on to the end of term, and soon I’ll be free to spend some months doing field work. Jack had offers to excavate Bronze-age sites in Britain and pre-Columbian sites in southern Canada, but the source of the Incan gold kept returning to nag him. I’ll talk to Dad, he told himself, as he pushed against the classroom door with his briefcase. The sudden thought that maybe he had left his revolver in it gave him a start as he dropped the bag on the desk. No sense looking for it now. If the students saw it, they would likely be terrified and the museum did not need students more terrified than usual. Looking over the lectern at dozens of nondescript faces in the usual crowd--serious students, to those more pleasantly bored with the subject matter, Jack thought again about why he got into academia. “It’s the field work,” he muttered half out loud. “Teaching is just a job and a paycheck!” The real payday comes in the field with new discoveries, and sometimes, with the right batch of students, even teaching in the field pays off! Just as he started to open his notes, he thought again about von Humboldt. He would have wanted to find the source of the Incan gold, with that inquisitive mind of his, and so do I. |

||